The worth of an object is commonly framed by way of its completeness. As people and as a museum, we like pristine issues and attempt to hold them that manner. If one thing breaks, we restore it. Whether it is damaged past restore, we could change it. And but, generally it’s the damaged, incomplete issues that yield the best insights into previous lives. On this weblog, Dr Matt Knight explores this concept by the therapy of bronze and gold objects from the Bronze Age in Scotland (c.2400 – 800BC).

A lot of what we discover throughout archaeological excavations are fragments of objects and supplies. A few of that is all the way down to the passing of time, however generally we discover issues that had been deliberately damaged or broken earlier than being deposited. How can we make sense of this deliberate destruction?

Why will we break issues?

We will begin by asking the query, why do folks deliberately break issues at present? Destruction is perhaps a social or political act, like vandalism or iconoclasm. It is perhaps superstitious, like breaking a bottle towards a ship for good luck. Generally a possession is damaged when somebody dies or when a relationship ends, symbolically breaking the hyperlink between the particular person and the item.

These concepts trace on the great vary of causes issues is perhaps destroyed and the symbolic nature of breaking issues. Breaking issues on this manner is an emotional act. The act of destruction itself takes on worth, whether or not for commemoration or catharsis.

The examples of Bronze Age objects under present that this isn’t unique to our trendy cultures. We will hint acts of deliberate breakage and deformation throughout human historical past.

Roll up! Roll up!

The primary object is, I hope you’ll agree, fairly spectacular. The Auchentaggart lunula from Dumfries and Galloway is a adorned gold collar, barely thicker than tin foil. It is without doubt one of the earliest items of goldwork from Scotland. It required entry to a good chunk of gold in addition to expertise to craft such a ravishing, fragile decoration – a real signal of standing.

Many lunulae had been buried full and undamaged, however the Auchentaggart instance was “folded collectively and rolled up nearly like a ball” earlier than burial. Curiously, this isn’t an remoted case. A lunula from Orbliston, Moray, was discovered “intently rolled up” and 16 examples from Eire had been additionally in all probability rolled or folded when buried. Some present indicators of getting been rolled and unrolled a number of occasions. This was reversible harm.

This all begs the query: why would you fold, roll and bury a chunk of your jewelry? Ornaments are often fairly private issues, however lunulae are by no means discovered with human burials. It appears the objects had been intentionally separated from the folks. Maybe rolling and folding ornaments could have been a part of this separation, bodily remodeling the objects to look completely different from how they had been worn.

This transformation may additionally be what made these objects appropriate for putting within the floor, though the existence of full examples reveals that this wasn’t a vital job. This was maybe a personalised response to particular person conditions.

Utterly incomplete

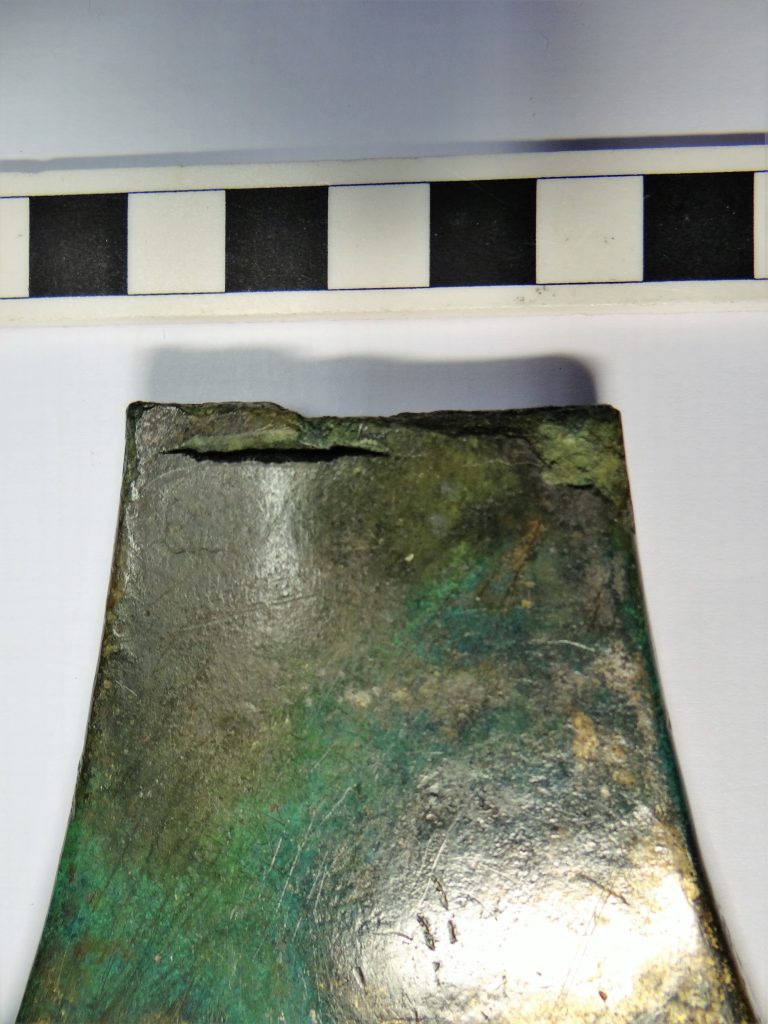

Different cases of harm are extra apparent. A hoard from Hill of Finglenny, Aberdeenshire, consists of 4 full axeheads and three axeheads intentionally snapped in half. The axes are fairly thick objects, and breakage would have been troublesome to attain should you didn’t know what you had been doing.

The axeheads wanted to be heated to excessive temperatures earlier than they had been struck with hammers and chisels, which might then trigger them to snap in two. All of this implies a pre-meditated choice to interrupt these axes that required materials data and appropriate instruments. In different phrases, harm was a selection and a selection that took vital effort. What motivated this selection? Why had been some left full and others damaged?

Analysis into these axes by Dr Rachel Crellin, amongst others, has highlighted varied indicators of use and put on, in addition to variations of their breakage. This means the axes had completely different histories of use and, presumably, possession main up the purpose of burial. These variations within the ‘life’ of the axes could have influenced which bought damaged and which didn’t. Nonetheless, each items of every damaged axe had been stored collectively on this hoard. This means there was symbolism in maintaining the unfinished, full. The variations in therapy replicate completely different values connected to the artefacts even inside a single hoard.

Destruction breeds creation

Lastly, we would contemplate how destruction of objects allowed the creation of one thing completely different totally. In the direction of the top of the Bronze Age, giant teams of metalwork had been sometimes fragmented and buried. Generally these had been damaged in preparation for recycling, however there are additionally circumstances the place destruction clearly went past this.

At Duddingston Loch, Edinburgh, as many as 50 swords and spears had been extensively bent, damaged and burnt earlier than they had been thrown within the loch, maybe over a number of events. At Peelhill Farm, Lanarkshire, one other hoard of weapons, together with 25 spears and one sword, noticed the identical therapy earlier than it was sunk into marshes.

The ‘sacrifice’, if that’s the proper phrase, of such substantial portions of weaponry on a big hearth would have been a dramatic occasion in its personal proper. The placing nature of destroying weapons was maybe a public and symbolic spectacle, presumably to finalise a battle and create a memorable occasion by which to mark it. Lengthy after the destroyed weapons had been forged within the water, the efficiency of their destruction and deposition could be remembered by the group.

Valuing harm

Broken objects give us new views on the dynamics of the previous and the folks concerned of their creation, destruction, and reminiscence. On the identical time, it encourages us to suppose extra rigorously about damaged objects within the current and what we see in museums. You is perhaps shocked to listen to you received’t see a rolled up lunula in a museum: they had been all unfolded and unrolled when found within the 18th and nineteenth centuries and are preserved of their unique unrolled state.

But for me, this obscures a key a part of the story of these objects. Damaged and broken items of axes, swords and spears rework our understanding of what these objects meant, and there may be large worth in appreciating them due to, fairly than regardless of, their broken state. Harm attests to the creation of a distinct type of worth by destruction, a lesson that applies simply as a lot to the Data Age because it does to the Bronze Age.

To study extra in regards to the destruction and deposition of metalwork in Bronze Age Britain, see Dr Matt Knight’s ebook, Fragments of the Bronze Age: The Destruction and Deposition of Metalwork in South-West Britain and its Wider Context, out there from Oxbow Books.

A Center-East Epic Paranormal #Fantasy

A Center-East Epic Paranormal #Fantasy

’Monsters within the wooden nip on the edges of her ideas.’

’Monsters within the wooden nip on the edges of her ideas.’