Stone steps washed with waves and selkie songs glitter within the late summer time gloaming. Roaring tides sweep in from all sides to batter the shore with ageless dedication, steadily devouring the remnants of cairn-raisers, Picts, Norse, and crofters with equal indifference. The west wind catches a string of hanging seashells put up by this season’s crew of archaeologists, filling the ruinous, long-silent halls with the music of the ocean. Right here, alongside the shores of the Eynhallow Sound in Orkney, eras and components construct into an unforgettable refrain. Be a part of Digital Media Content material Producer David C. Weinczok on a journey alongside the shores of Orkney’s Eynhallow Sound.

Rousay and the Westness Stroll

Alongside the one and a half-mile shorescape referred to as the Westness Stroll on the island of Rousay, time is something however linear. Treading this sliver from one finish to the opposite, you’re hurtled by way of greater than 5,000 years of settlements. Durations of historical past tidily divided from one another on paper crumble into and rise out from one another.

At Swandro, which loses a bit of of itself to the ocean yearly, Iron Age buildings are topped by a Pictish smithy and surrounded by the intermingled ruins of Norse halls, late medieval farmhouses, and cleared nineteenth century crofts.

The historic knot turns into even tougher to untangle since virtually the whole lot was constructed from Rousay flagstone. Slabs of this extraordinarily sturdy, multi-purpose stone are prepared to make use of as soon as pried with relative ease from their supply. They proved simply as helpful to the individuals whose bones stuffed the stalls of Midhowe Cairn in 3,500 BC because it was for the tenant farmers who constructed their houses on the overlooking slopes lower than two centuries in the past.

A fertile strip wraps spherical Rousay, giving means rapidly to steep slopes resulting in an upland zone of heather and protruding stone. On Rousay’s southern shore the shoreline is dotted at virtually common intervals with the grass-covered stays of brochs. Not less than 13 of those Iron Age stone towers as soon as lined the Eynhallow Sound, a frightening prospect for any hostile vessels and a potent expression of energy for all to behold. The grandest of those ruins is Midhowe Broch on the western terminus of the Westness Stroll.

In the same string, alongside the very line the place lowland provides method to upland (although this divide displays trendy land use) are a succession of chambered cairns with engaging names – Blackhammer, Taversoe Tuick, and the Knowe of Yarso to call a number of. Discover a 3D mannequin of the Knowe of Yarso from the College of the Highlands and Islands Archaeology Institute on Sketchfab right here.

Midhowe Chambered Cairn is one exception to this neat association, being positioned on the shoreline subsequent to Midhowe Broch. It was constructed round 3,500 BC, which means that extra time handed between its development and the constructing of Midhowe Broch than between the broch and us at present. Lots of the brochs and cairns had been excavated within the early by way of mid-Twentieth century by James Petrie and Walter Grant, yielding an enormous array of finds together with human stays, pottery, animal bones of attainable totemic significance, and Neolithic stone axeheads.

Bronze and iron had been labored at Midhowe Broch, which – just like the Broch of Gurness inside view throughout the Eynhallow Sound – had a village surrounding the broch tower. These weren’t the ‘distant’ or ‘easy’ locations that trendy writers too typically describe such locations as, however subtle and productive centres dwelling to imaginative, resourceful, and well-connected communities.

Although little might be stated with certainty in regards to the look and beliefs of Rousay’s broch dwellers, one exceptional survivor from elsewhere in Orkney provides us a uncommon glimpse – the Orkney Hood. It’s the solely full piece of clothes to outlive from earlier than the medieval interval in Scotland. Be taught its story within the video under.

Westness cemetery

In 1963, Ronald Stevenson was burying a useless cow close to the shore at Moaness, a part of Westness, when his shovel struck one thing sudden. The unusual issues pulled from the soil had been despatched to the Nationwide Museum of Scotland, who promptly despatched Audrey Henshalla crew to excavate. They revealed the flowery burial of an grownup girl and new-born little one. Mom and little one virtually definitely died within the act of beginning. They had been removed from alone – their grave was a part of one crucial Viking Age cemeteries exterior Scandinavia.

One of many girl’s possessions was a bead necklace, varied items of which had Irish, Anglo-Saxon, Frankish, Frisian, and Baltic origins. Two tortoise-like oval brooches rested under her shoulders, very similar to these discovered among the many grave items of one other distinguished Norse girl’s burial throughout the Eynhallow Sound on the Broch of Gurness. The frilly Westness brooch, made from silver, amber, pink glass and gold inlay, additional marks her out as somebody of excessive standing.

The long-disintegrated scarf her individuals buried her in was mounted by a hacked fragment of an Insular Christian shrine or e-book cowl, modified into a brooch. As Glenmorangie Researcher and creator of Crucible of Nations, Dr Adrián Maldonado, noticed, she “had the entire Viking world in her grave.”

The Westness cemetery contained 32 burials courting from the seventh by way of eleventh centuries, together with two boat burials of older Norse males. At first, these males’s graves appear to embody the favored picture of Viking-age violence. Grave items included the entire accoutrements of battle: a adorned sword, a broad-bladed iron axe, iron spearhead, protect boss, and arrowheads. Each males had arthritis, chipped tooth, and heavy put on and tear of their arms. Every little thing suggests these had been warriors who died previous their prime. Nevertheless, not all Norse males’s graves containing weapons are essentially these of warriors, as these objects had wider symbolic significance and weapons buried with an individual didn’t essentially belong to that particular person.

Alongside these finds, nonetheless, had been many others that solid their society in a extra settled, peaceful gentle. In the identical grave that contained the above arsenal was an iron ploughshare. Others had been buried with sickles, a strike-a-light, antler combs and gaming items. By the eleventh century, the times of marauding Vikings had been, with a number of exceptions, long gone. The Norse in Orkney had transformed to Christianity, and distinguished residents of the world are named within the thirteenth century Icelandic saga, Orkneyinga Saga, not as blood-soaked warriors however as influential farmers. The vast majority of individuals in Viking-age Orkney would have met non-violent ends.

Certainly, the useless of Westness have at the least one factor in widespread with trendy archaeological approaches: they’ve little regard for tidy, binary identities. The Norse burials coexist alongside earlier Pictish burials, with no obvious try by the previous to disturb the stays of the latter. Going a lot additional again, new analysis has proven that lots of the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age ancestors of Orkney’s Picts had been themselves incomers from Continental Europe by the use of the British mainland.

Orcadian poet and storyteller George Mackay Brown, who typically centred his timeless tales on Viking-age Rousay and the Eynhallow Sound, noticed, “The individuals of Orkney at present are a mingled weave.” So, too, had been many Orcadians – Pict, Norse, Scots, and in any other case – of the previous.

Cubbie Roo’s Citadel and the island of Wyre

Throughout a slender but temperamental stretch of water from the jap shore of Rousay is Wyre, an arrowhead-shaped island so low-lying that it appears a single excessive wave might wash over it.

Wyre’s inhabitants is now simply 5, although it was not all the time so sparse. As an example, excavations directed by Dan Lee and Antonia Thomas of the College of the Highlands and Islands on the Braes of Ha’Breck discovered a Neolithic complicated containing the charred stays of Neolithic cereals courting to c.3,300 – 3,000 BC. This was in all probability from an prolonged household group dwelling in Wyre’s western edge. On condition that the household group would seemingly not have been alone in Wyre, and that the medieval interval noticed even larger exercise in Wyre, it illustrates how elements of the Highlands and Islands are much less populated now than at many factors in historical past.

Probably the most well-known medieval resident of Wyre was Kolbein Hruga, a twelfth century Norseman who later handed into legend as a fearsome big referred to as Cubbie Roo. In Orkney dialect, ‘cubbie’ is a phrase for a creel or basket-work service often known as a ‘cassie’. Cubbie Roo is claimed to have met his finish when a stone causeway he was constructing between Wyre and Rousay collapsed, burying him within the rubble. This story gave its identify to a cairn on the Rousay shore trying throughout to Wyre, ‘Cubbie Roo’s Burden’.

Kolbein was an innovator. Upon a small whaleback hill are the ruins of Cubbie Roo’s Citadel, seemingly one of many oldest stone castles in Scotland. Throughout the Viking Age, Wyre was plugged right into a community of buying and selling and raiding that reached out from the North Sea so far as the Japanese Mediterranean. The most recent castle-building kinds of Europe didn’t go unnoticed by Orcadian venturers, the place they had been tailored to native circumstances and supplies. Cubbie Roo’s Citadel is now diminished to its floor flooring, however would as soon as have stood three tales excessive and its seemingly white-harled outer partitions would have shone throughout the Eynhallow Sound.

It’s seemingly that Kolbein had his citadel constructed over the stays of an Iron Age broch which might have been 1,000 years previous or extra in his time. It’s simple to identify similarities between the citadel’s structure and the Broch of Gurness, among the finest surviving broch websites positioned on the Mainland shore of the Eynhallow Sound.

Finds from Cubbie Roo’s Citadel and speedy space round it together with St Mary’s Chapel communicate to make use of over a number of centuries at the least, together with an annular bronze brooch, fragment of chain-mail, and a part of a bronze hawk’s bell. In a report on Orkney revealed in 1774, James Fea wrote, “The Hawks of this nation are deemed the best on this planet, insomuch, that the King’s Falconer sends individuals yearly to Orkney, to take them up; generally within the month of Might, once they brood.” May this bell be a legacy of this prestigious follow?

Eynhallow, the ‘vanishing island’

The Atlantic Ocean and North Sea are locked in endless battle within the Eynhallow Sound. This conflict creates roosts, sudden and horrible chimeras of wave and wind that may sink ships right away. They seem as white-crested partitions throughout the island of Eynhallow. As soon as dwelling to a monastic group and several other households, the final everlasting inhabitants of Eynhallow had been evicted in 1851 following a typhoid outbreak.

Eynhallow is a ‘vanishing island’, typically misplaced to sea mists and regarded in Orkney lore because the remnants of Hildaland, the magical realm of the amphibious Fin-Males who had been held chargeable for disappearances, fishermen’s misplaced catches, and different misfortunes. To once more quote George Mackay Brown, he supposed that this magical realm had not been seen “since fishermen folded up their sails and put in petrol engines of their boats.”

No particular person might make touchdown on Eynhallow until they by no means appeared away from it and grasped chilly iron of their arms, comparable to a nail or cruik. Such was the magic of the Fin-Males that Orcadian chroniclers insisted animals would immediately seize up and die on touching its soils. Maybe the spell had worn off by the nineteenth century, when the island was used for summer time sheep grazing.

The one inhabitable constructing in Eynhallow at present is a ranger’s lodge. Remarkably, it contained cushions and coverings made from Morris materials (at the least, as of the mid-2000s), introduced over from Westness Home in Rousay or Melsetter Home in Hoy.

But, regardless of Eynhallow’s folkloric position as an island of thriller, not so way back (within the grand scheme of issues) it was not an island in any respect. When the primary post-glacial settlers arrived in Orkney, sea ranges had been round twenty metres decrease than they’re now. Orkney was then two giant islands, which means that the primary individuals to reach in Rousay didn’t take a ship to succeed in it – they walked.

In our personal instances, the Eynhallow Sound’s waters could also be fierce, however they’re nonetheless shallow sufficient to see the underside in clear circumstances on the ferry from Tingwall to Rousay. Throughout this brief voyage you’re virtually definitely crusing over sunken stays of historical human exercise. Rising sea ranges, ensuing largely from local weather change, are a significant risk to Orkney’s historic websites. Almost 2,000 of them, together with many in Rousay and Wyre, are actively being misplaced as a consequence of erosion and inundation.

Reflections from the Sound

It was in landscapes like these, crammed with grassy mounds concealing remnants of the traditional world, that Scottish archaeology as we all know it was born. The array of finds from the excavation of websites such because the Broch of Gurness, Midhowe Chambered Cairn, and Taversoe Tuick led to the popularity of Stone, Bronze, an Iron Ages, with a lot of them proving to be older than conventionally believed by centuries and even millennia. Investigations by members of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, based in 1780, shaped the idea of the collections of the Nationwide Museum of Antiquities of Scotland, the precursor of Nationwide Museums Scotland.

To others, together with writers, poets, craftspeople, and artists, the “mingled weave” of historical past on the shores of the Eynhallow Sound was (and stays) a bottomless effectively of inspiration. Individuals as diverse as Edwin Muir, Robert Rendall, Eliza Burroughs, and Will Self have drawn from it. Many trendy archaeologists together with Anna Ritchie, the late and vastly influential Caroline Wickham-Jones, and Nationwide Museums Scotland’s personal Dr Hugo Anderson-Whymark have made many insights into the world and Orkney extra broadly. The Norse period specifically continues to encourage cultural actions in Orkney, together with the St Magnus Worldwide Competition and the Orkney Storytelling Competition.

For anybody who finds function and marvel within the tales of the previous, exploring the shores of the Eynhallow Sound because the roosts roar and seals sing, flanked by a conglomerate of websites spanning over 5,000 years, is an expertise by no means to be forgotten. Armed with the tales and data of the objects this place yielded (and, for further immersion, a duplicate of the Orkneyinga Saga in hand) this panorama is not like another I’ve identified. Who is aware of – maybe you’ll even catch a glimpse of Hildaland by way of the mist.

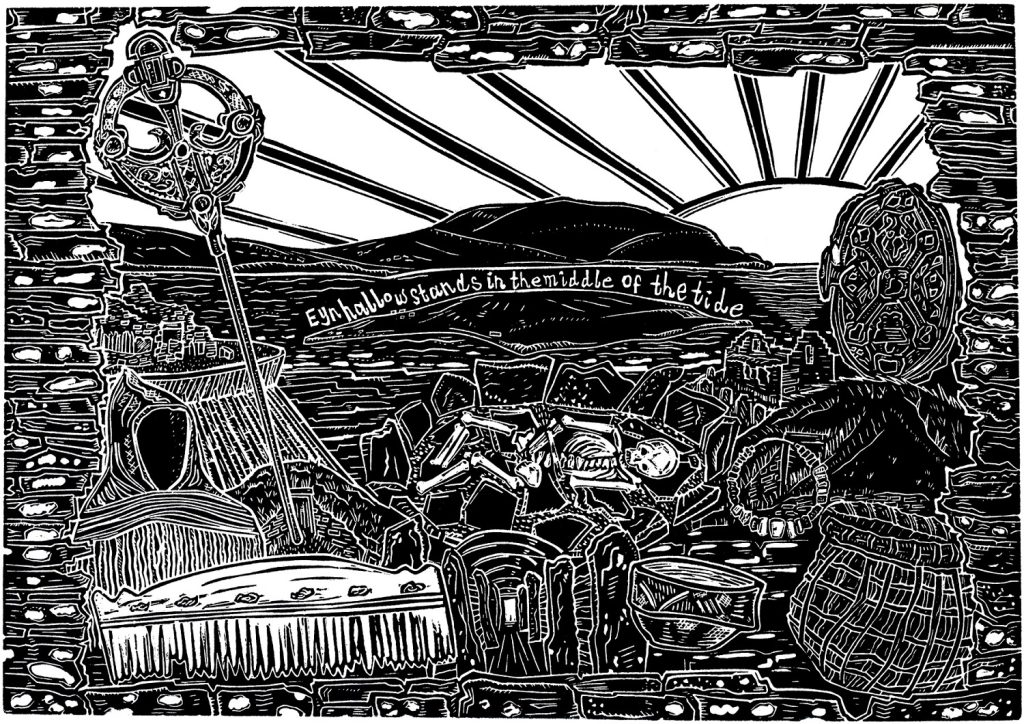

Watch the inventive strategy of Pamela Scott, creator of the linocut, within the time lapse video under.

The six-part Objects in Place weblog collection will proceed in April, with half 4 heading to the embattled coronary heart of Scotland, Stirling. Half 5 in June goes to Tantallon Citadel, East Lothian, for some castle-based historical past. Half six in August will deliver the collection to a conclusion with a particular place very near us – Greyfriars Kirkyard in Edinburgh. Dundee-based illustrator and printmaker Pamela Scott has been commissioned to supply a novel art work for every installment. When you haven’t already, learn half one about Kilmartin Glen, Argyll, right here, and half two in regards to the Eildon Hills and Melrose right here.