Each a part of Scotland is historic, with tales for the telling. Whether or not rural or city, landscapes and communities are the final word supply of the objects we accumulate and show. But, it’s simple to be so preoccupied with the objects themselves that we lose sight of the place these objects had been made, used, discovered, and given which means. On this, the primary of a six-part weblog sequence by historian, author, and Digital Media content material producer David C. Weinczok, we zoom out to replicate on the locations past the glass circumstances.

Within the dappled morning gentle, Kilmartin Glen awakens. The solar’s first tendrils embrace the Moine Mhòr – the ‘Nice Moss’ – from the Crinan Canal to the nice glacial terrace down which prehistoric waters surged. Shadows lengthen like fingers rising from the bottom of the standing stones of Nether Largie and Ballymeanoch. The grooves of 5,000 year-old carvings hewn into rocky canvases are thrown into sudden, stark reduction. The snaking River Add is warmed on its journey previous an historical hilltop capital into the turbulent Sound of Jura. A rooster calls out from the farm to the north, echoing over the parapets of Carnasserie Fortress. Within the coronary heart of the village the church door creaks open, the graves of warriors 500 years gone ready for the day’s first footsteps to fall on them.

Kilmartin Glen in Mid-Argyll is without doubt one of the most archaeologically prolific locations in northwest Europe. In a low-lying space some 5 miles lengthy and huge and surrounded by modest hills like an awesome dish, there are over 800 historic websites. On the maps of the Royal Fee on the Historical and Historic Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS), no different space of Argyll is lit up by so many remnants of the previous. But, not like the Coronary heart of Neolithic Orkney centred on the Ness of Brodgar and Maeshowe, mainstream fame largely eludes it.

Our collections, together with objects occurring mortgage to the newly redeveloped and vastly expanded Kilmartin Museum in 2023, assist inform the story of this extraordinary place. In flip, attending to know Kilmartin Glen higher helps us put these objects in context.

The Nice Moss

Inside the narrative of Kilmartin Glen, the raised lavatory of the Moine Mhòr (pronounced ‘Moyn ya-vore’) is each hero and antagonist. Between 4,000 and a couple of,500 years in the past Scotland’s local weather markedly deteriorated. Elevated rainfall and dropping temperatures led to degraded soil high quality and a discount in vegetation, in flip lowering herbivore populations similar to deer. Deep peat shaped in beforehand arable lands, and upland settlements throughout Scotland had been deserted for milder, extra simply provided areas.

The Moine Mhòr devoured ten-foot-tall standing stones, leaving solely their peaks seen to their builders’ descendants, like skerries in a sea of salt and peat. They might not be absolutely revealed once more till the nineteenth century, when Enchancment schemes carried out by the Malcolms of Poltalloch – funded largely by income from Jamaican sugar and tobacco plantations labored by enslaved individuals – reclaimed land for agriculture.

But whereas the Nice Moss lengthy marked the boundaries of human habitation, additionally it is a champion for wildlife and the pure atmosphere. Like Sutherland’s Stream Nation in miniature, it captures huge quantities of carbon dioxide and hosts a flourishing wetland ecosystem that in the present day delights residents and guests alike. It’s one among Europe’s most delicate and threatened habitats, its future now hopefully secured by its standing as a Nationwide Nature Reserve.

Dunadd, coronary heart of the Scots

Dunadd is a spot whose subtlety within the panorama belies its significance. At simply 54 metres excessive, it’s removed from the tallest hill round. Considered throughout the flatness of the Moine Mhòr, Dunadd is nearly camouflaged by the a lot greater ridge instantly to the east. But this modest stone outcrop was one of the vital essential websites within the crucible of countries from which the early Kingdom of the Scots emerged.

Dunadd was a serious energy centre of Dál Riata, the Gaelic-speaking kingdom established on the west coast of Scotland through the sixth century AD. Nevertheless, occupation and fortification of the hill goes way back to 200 BC. Close to Dunadd’s summit, with sweeping panoramic views, is a footprint in stone, used throughout king-making ceremonies all through the Gaelic-speaking world. Comparable footprints could be discovered at Finlaggan in Islay, Camusvrachan in Glen Lyon, Southend within the Mull of Kintyre, amongst others.

In all my visits to Dunadd, I’ve by no means seen anybody in a position to withstand the urge to drag off their footwear and socks and see if their foot matches, myself included. The print is in reality a forged meant to guard the unique, however such are the compromises we make between authenticity and preservation.

By way of the coastal waterways resulting in the River Add, which weaves via the Moine Mhòr, the world got here to Kilmartin Glen. Adomnan’s seventh-century chronicle Lifetime of Columba tells of French ‘wine-ships’ docking close to Argyll’s caput regionis, ‘the top of the area’, interpreted by pioneering Argyll archaeologist Marion Campbell as referring to Dunadd. The hillfort was as soon as accessible by water, with small boats as soon as capable of sail up the River Add almost to its base.

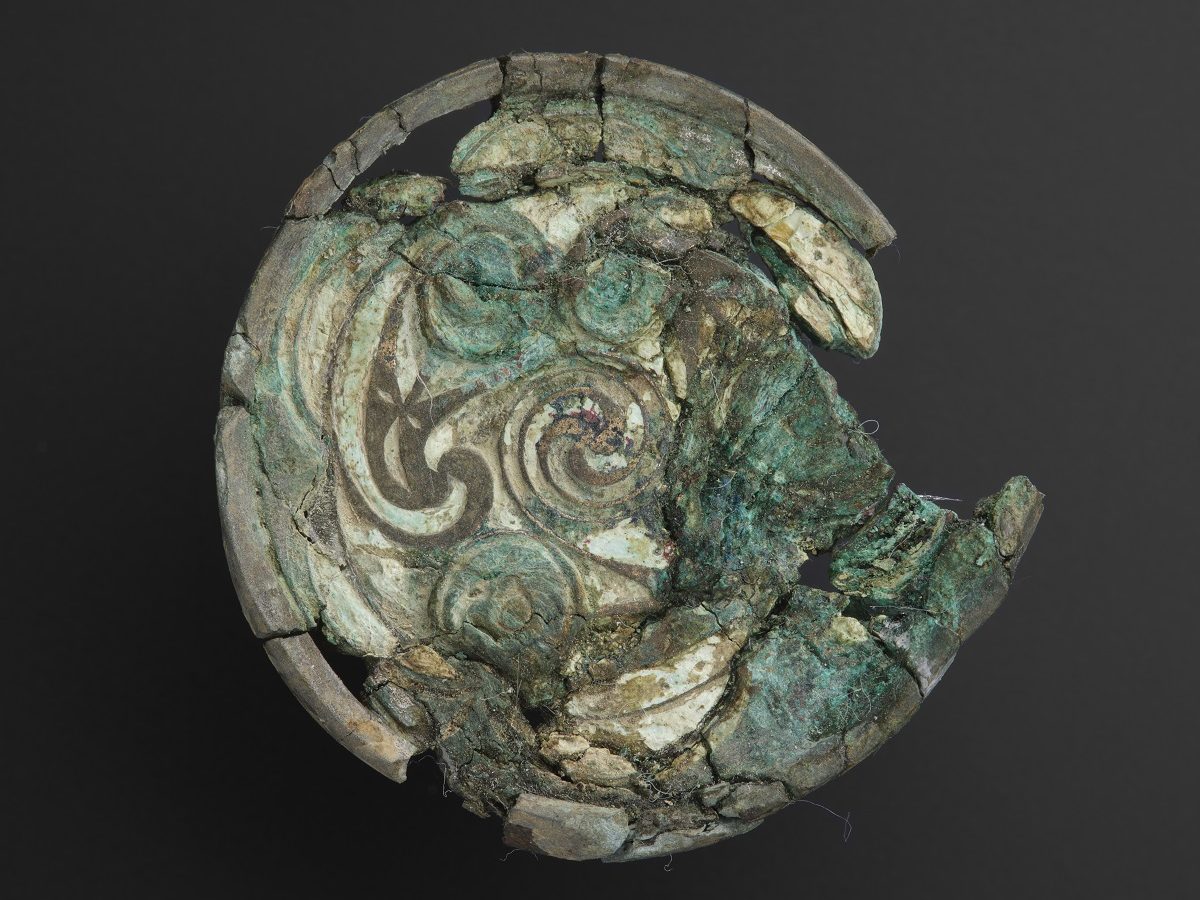

Throughout early twentieth century excavations funded by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, an enamelled interlace disc from c.575-850 of potential Frankish origin was discovered right here. There was additionally orpiment, a sulphide of arsenic used as a yellow pigment within the illumination of early Insular Christian manuscripts. Assets for the illumination of manuscripts had been probably imported to Dunadd after which despatched on to Iona, connecting Kilmartin to the broader North Atlantic monastic world. Our collections comprise a tessera from a Byzantine glass mosaic with gold leaf, demonstrating that connections prolonged to the guts of the Mediterranean and past.

Management over the manufacturing and distribution of bronze objects was, because the title implies, one of many hallmarks of energy within the Bronze Age. Kilmartin Glen was influential on this revolution, and continued to be a centre of bronze working till nicely into the Early Medieval interval. Finds now in our collections embrace a gold and garnet stud and sheet bronze fragment imported from Northumbria c.600-700 AD, an enamelled copper alloy disc from a dangling bowl c.575-850 CE, a loop-headed pin imported from Eire, and two moulds for creating penannular brooches. Treasured steel dress-fasteners like these, for instance the Hunterston Brooch, exchanged palms all through the Insular world through the Early Medieval and Viking ages.

The Linear Cemetery

Strung out just like the dots of a map’s path via the centre of Kilmartin Glen are a line of cairns, collectively referred to as the ‘Linear Cemetery’. 5 of an authentic seven cairns survive to various levels in the present day. Some could be entered, although that was by no means the intention, whereas others are decreased to rubble. The hills that slim the glen’s northern boundaries urge the eyes and momentum of travelling toes in the direction of the point of interest of the cairns. Particular person websites throughout the historic panorama of Kilmartin Glen are intimately interconnected, although some monuments predate others by hundreds of years.

Bronze Age spherical cairns symbolize an essential shift in historical funerary practices. Whereas earlier cairns had been raised for teams of individuals, these within the Linear Cemetery had been for people. They’re additionally the earliest funerary monuments that frequently comprise grave items for contemporary archaeologists to find. This shift coincided with an finish to the creation of recent rock artwork websites, attributable partially to a time of climactic degradation.

Inside Glebe Cairn, adjoining to Kilmartin Museum, a jet necklace of great worth and intricacy was discovered with a girl’s skeleton. Her luxurious grave items additionally included a superbly embellished meals vessel, one of many best in Scotland that drew inspiration from connections with Eire. The necklace was later misplaced in a fireplace which consumed close by Poltalloch Home, house of the Malcolms of Poltalloch. Our collections comprise the same jet necklace and bracelet present in one other Bronze Age burial within the glen.

Kilmartin’s Bronze Age cairns have yielded quite a lot of vessels, together with early kinds of Beaker vessels, indicating the arrival of recent peoples, concepts and kinds of fabric tradition. It was within the Bronze Age that Kilmartin Glen actually flourished, with a lot of its best-known monuments together with the Linear Cemetery and Temple Wooden taking their present type.

Symbols in stone

Not all archaeological finds could be faraway from the bottom that holds them. Some are woven into the land itself. Scotland’s Rock Artwork Mission (ScRAP) has recorded 332 rock artwork panels in and round Kilmartin Glen, accounting for a staggering 10% of all recognized rock artwork websites in Scotland. Most had been made between 4,000 – 2,500 BC, totally on gently sloping, south-facing rock outcrops.

In contrast to funerary monuments and standing stones, which had been normally meant to be seen from far-off, rock artwork was most frequently created away from well-worn paths. Maybe they had been meant to retain an intimacy for the customer, or to be recognized solely to native communities. As with the deliberate destruction and depositing of bronze objects in lochs and bogs, the creation of rock artwork was probably a communal occasion supposed to endure in collective reminiscence.

The which means of those motifs is now misplaced to time. The identical can’t be stated of their significance, nevertheless, as Kilmartin’s fashionable residents enthusiastically show their very own renditions of them in store home windows, roadside graffiti, and regionally produced items. It’s a uncommon design that may boast reputation after greater than 6,000 years.

In Kilmartin Glen, dynamic arrays of rock artwork motifs similar to cup-and-ring marks are discovered at Achnabreac, Kilmichael Glassary, Cairnbaan, and Ormaig. Whereas none of our rock artwork examples of this kind hail from Kilmartin Glen, we do have one other instance of a message in stone that we are able to perceive. Ogham was an Early Medieval alphabet used all through Eire and the west of Britain. It’s written as stroke-marks, as seen in our instance from Poltalloch and on one other carved slab atop Dunadd the place the Ogham is accompanied by a carving of a boar.

Kilmartin previous and future

Although our objects put the highlight on prehistory and the Early Medieval interval, the story of Kilmartin Glen after all doesn’t finish there. Carnasserie, Kilmartin, and Duntrune castles, in addition to the Hebridean-style grave slabs in Kilmartin Churchyard, communicate to potent happenings all through the Center Ages. The primary printed e-book in Gaelic, a translation by Bishop Carswell of John Knox’s E book of Widespread Order, was made at Carnasserie. The Highland Clearances dispersed many Kilmartin residents to Glasgow, the Americas, and past, whereas the exploitative windfalls of colonialism drove the constructing of mansions and an more and more tangible human dominance over the land within the age of ‘Enchancment’.

Kilmartin’s previous, as illuminated by our objects, was formed by drastic environmental change, ebbs and flows within the distribution of energy, and the creation of issues of staggering magnificence in occasions of each a lot and hardship. Issues which as soon as appeared everlasting have proved ephemeral, whereas others created in and for a selected second have endured lengthy past their makers. Let that be knowledge of Kilmartin Glen, and of the objects from it.

Get pleasure from a minute-long have a look at artist Pamela Scott’s rendition of Kilmartin Glen.

Music credit score: ‘Lengthy Highway Forward B’ by Kevin MacLeod is licensed underneath a Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 license: Supply

The six-part Objects in Place weblog sequence will proceed in November, with half two trying on the space round Newstead and the Eildon Hills within the Scottish Borders. Half three in December covers Stirling. Half 4 in January 2023 goes to Westness, Rousay, in Orkney. Half 5 in February is all about Threave Fortress, Dumfries and Galloway. Half six in March brings the sequence to a conclusion with someplace very near us – Greyfriars Kirkyard in Edinburgh. Dundee-based illustrator and printmaker Pamela Scott has been commissioned to supply a novel art work for every installment.