2022 is a landmark 12 months in Egyptology. It’s been 200 years because the decipherment of hieroglyphs, which unlocked entry to written sources from historical Egypt, and 100 years because the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun, whose splendour additional fuelled international Egyptomania. Many have celebrated these milestones, however it is usually an apt second to mirror on the historical past of Egyptology and its colonial origins. Principal Curator Margaret Maitland does simply that and explores among the current work we’ve been doing on this space.

Historical Egyptian objects are so ubiquitous within the UK that they’ve turn into virtually synonymous with the very thought of museums themselves. Consequently, we regularly take the presence of Egyptian materials without any consideration. Nonetheless, few are totally conscious of the advanced histories of those collections. Many colleges within the UK now educate pupils about historical Egypt, however virtually none deal with Britain’s historical past of colonial rule in Egypt.

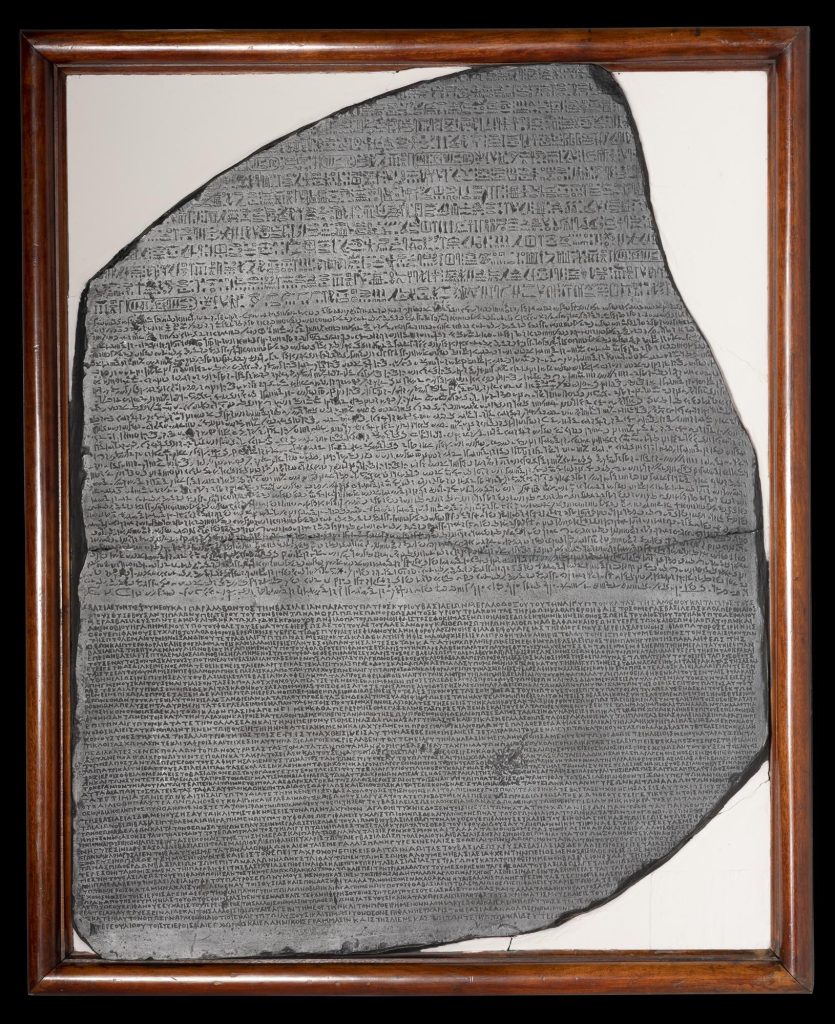

Probably the most iconic historical Egyptian objects each have un-taught histories. The Rosetta Stone that proved key to decipherment was initially discovered by the invading French military after which seized by the British military. And the tomb of Tutankhamun was excavated whereas Egypt struggled to determine its independence from British navy management.

Studying the Rosetta Stone

One of many 4 authentic casts of the Rosetta Stone, made in London in 1802 to encourage decipherment efforts throughout the UK, is on show within the Historical Egypt Rediscovered gallery on the Nationwide Museum of Scotland. The decipherment of the Rosetta Stone is usually introduced as a triumph of European scholarship, however the story is way more advanced.

When it was first found, carved with the identical decree written in three languages (historical Greek, hieroglyphs, and a late type of historical Egyptian writing referred to as Demotic) its potential to unlock the which means of hieroglyphs sparked a global race. The French scholar Jean-François Champollion made his breakthrough in 1822, nevertheless it’s vital to keep in mind that the actual key to understanding hieroglyphs was Egyptian.

A vital think about Champollion’s understanding was the truth that he discovered the Egyptian language generally known as Coptic (straight descended from historical Egyptian) on the recommendation of the distinguished Egyptian professor Rufa’il Zakhûr. This led to Champollion’s realisation that historical Egyptian have to be written phonetically, somewhat than solely symbolically. Finally, hieroglyphs weren’t simply an summary code to be cracked, it was about discovering understanding by communication.

The curse of Tutankhamun?

When the tomb of Tutankhamun was found 100 years later in 1922, folks all over the world have been captivated by the golden ‘treasures’ that it contained. The media on the time promoted the sensationalist thought of a ‘curse’. However the actual curse has been the distorting affect that the burial’s splendour has had on public expectations of historical Egypt ever since.

Though the Nationwide Museum of Scotland has a number of objects associated to Tutankhamun on show, analysis into our collections historical past means that there was intense strain on museum shows to match the magnificence of Tutankhamun’s treasures. Former Keeper Cyril Aldred, whose historical Egypt gallery opened at our Museum in 1972 (the identical 12 months because the well-known Tutankhamun exhibition in London), even went as far as to make a replica of one in every of Tutankhamun’s golden pectorals. Sadly, whereas we’ve been enthralled by pharaohs and golden treasures, the tales of odd historical Egyptians have all too usually been ignored or erased.

On this anniversary 12 months, it feels particularly well timed to contemplate the historical past and way forward for Egyptology and museums. Not too long ago, Nationwide Museums Scotland has been reflecting on how we analysis and symbolize imperial and colonial pasts and the way the legacies of those nonetheless affect our museums immediately. We’ve got been researching the provenance of our Egyptian and Sudanese collections, in addition to the historical past of museum gathering and show extra broadly and incorporating this info into our shows and public outputs.

Revised shows

We’ve been reviewing current panels and labels on the Nationwide Museum of Scotland and making modifications to handle historic bias and colonial legacies. For instance, this historical Egyptian coffin and mummified man are on show in our Amassing Tales gallery, which was beforehand referred to as Discoveries. The previous label targeted on the Scottish colonial official and engineer Sir Colin Scott Moncrieff, who was concerned in dam-building tasks on the Nile and introduced again the coffin and mummified man as souvenirs.

The main target of the brand new label is to lift consciousness of how historical Egypt was co-opted into the thought of ‘Western civilisation’, disconnecting Egypt’s historical heritage from fashionable Egypt and from Africa. A part of this appropriation was the acquisition of an growing variety of objects by European collectors who framed their gathering as a obligatory act which “saved” the antiquities from fashionable Egyptians.

To counter this, we embrace a citation from the Egyptian scholar Rifaa al-Tahtawi, demonstrating that Egyptians have been invested of their historical heritage, even within the nineteenth century:

“These antiquities are the decoration of Egypt, and it shouldn’t be allowed that Egypt be stripped of its finery by sightseers. These monuments stay a historical past awakening to all previous ages, they inform us one thing of those that lived earlier than.”

Modern gathering

We hope to raised symbolize fashionable Egyptian views and broaden audiences’ perceptions of Egyptian heritage by growing our modern gathering in Egypt. For instance, a current addition to the gathering is a face masks made in Cairo within the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The fashion of ornament is named khayamiya, a conventional type of hand-stitched textile appliqué ornament, presumably way back to the historical pharaonic interval. Khayamiya is solely made within the Road of the Tentmakers (Shari’a al-Khayamiyya) in Cairo, a historic lined market constructed within the seventeenth century. As we speak, a lot of their dwindling commerce depends on tourism, which has been devasted by COVID-19. In response to the disaster, artist Essam Ali turned to creating protecting face masks and promoting them on-line.

The Eye of Horus (wedjat) motif on this explicit masks is an historical Egyptian amuletic image of safety and therapeutic, extremely applicable for the masks’s operate to guard towards illness. The image invoked a type of protecting magic related to the god Horus, whose eye was injured after which restored. This masks, and the work of khayamiyya-makers extra broadly, is only one instance of how Egyptians have been reclaiming their historical heritage.

Outreach actions

We’ve had the privilege to companion with the AHRC-funded undertaking ‘Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage’, led by Heba Abd el Gawad and Alice Stevenson. The undertaking has sought to speak the legacies of British archaeology in Egypt, to create alternatives for dialogue with fashionable Egyptian communities, and to amplify Egyptian voices. This has concerned collaboration with Egyptian comedian artists, on-line engagement with communities in Egypt by social media, WhatsApp teams, and on-line occasions, and the creation of an internet useful resource in colloquial Egyptian Arabic.

It’s clear that our audiences in Scotland additionally need to be taught extra about these advanced histories. Earlier this 12 months, we delivered the Museum’s first ever on-line Colleges Meeting to hundreds of pupils in over 130 colleges throughout Scotland. Pupils have been requested to vote on which questions they needed to ask us, and it was putting that the query with essentially the most votes was about how the museum had acquired its assortment of historical Egyptian objects. This introduced a welcome alternative to speak in regards to the historical past of gathering in Egypt and Sudan.

Contemplating the historical past of Egyptology, it’s maybe unsurprising that a lot of our very understanding of Egypt’s historical previous has been colored by colonial-era biases. For instance, the intact burial group of the ‘Qurna Queen’ has fascinated students because it was excavated over 100 years in the past, however bias has hampered understanding of the objects and the id of the royal girl. A concentrate on categorising the lady’s ethnic id and the objects in her burial as both Egyptian or Nubian illustrates how usually Egyptology has approached Egypt’s southern neighbour, Nubia, as ‘international’, somewhat than contemplating the proof the burial presents for shared elements of Nile Valley cultural heritage. Our current on-line occasion for UK Black Historical past Month was an vital alternative to showcase historical Nubian historical past and tradition and its vital affect on Egypt. You’ll be able to watch a recording of the occasion free of charge on our web site.

Ongoing analysis

In a few of our not too long ago printed work, we’ve mirrored on the function that restoration performed within the Museum’s historic shows of the twentieth century. We’ve explored the ensuing moral concerns that we confronted in conservation work for the event of our new Egypt gallery, which opened in 2019.

Historical Egyptian objects are sometimes exceedingly well-preserved, however the majority of the Museum’s Egyptian collections have been archaeological fragments from British excavations accepted for export as ‘minor antiquities’ or ‘duplicates’. Nonetheless, the general public’s heightened expectations from the treasures of Tutankhamun in all probability elevated strain to hold out intensive restoration work in an try and return objects to a ‘pristine’ state.

The intention to show an ideal Egyptian previous was certain up with problematic ideas of historical Egypt as foundational to ‘Western civilisation’, with curators and conservators from Europe and the US introduced as important to its understanding. Typically, the conservation supplies used have been discovered to be readily reversible and our Artefact Conservation group eliminated the vast majority of the extra deceptive restorations. However some objects stay eternally altered by their transformation into museum shows.

The historical past and ethics of gathering and show are points that we’’re persevering with to discover in our newest tasks. My ongoing analysis undertaking goals to contextualise the work of the revolutionary Scottish archaeologist Alexander Henry Rhind in Egypt. In 1835, Egypt banned the export of Egyptian antiquities with no allow (one of many oldest heritage safety legal guidelines on the planet). Throughout my analysis it grew to become obvious that the practicalities of this allow system hadn’t been studied earlier than. To raised perceive the context by which Rhind was given permission to excavate, I’ve been investigating Egypt’s early heritage safety efforts. I’ve additionally been figuring out Rhind’s Egyptian collaborators. He acknowledged them as ‘skilled and knowledgeable investigators’, however their vital contributions have been subsequently downplayed by later Egyptologists.

Our very personal Dr Dan Potter, Assistant Curator of the Historical Mediterranean, has not too long ago began an Arts and Humanities Analysis Council-funded Analysis, Improvement and Engagement Fellowship referred to as ‘Shopping for Energy: The Enterprise of British Archaeology and the Antiquities Market in Egypt and Sudan 1880-1939’. That is the primary totally funded analysis undertaking to concentrate on the involvement of British archaeologists within the antiquities market in Egypt and Sudan and the affect of this observe on museum collections.

Our collaborative doctoral award-funded PhD undertaking with scholar Giulia Marinos based mostly on the College of Glasgow is focussed on the historical past of Scottish museum shows of Egyptian collections within the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, together with analyzing how Britain’s involvement in empire formed these shows.

Though the legacies of the previous 200 years weigh closely, there’s clearly an urge for food to be taught extra about these histories, to listen to new and totally different tales, and to work extra collaboratively. Hopefully these and different ongoing tasks will assist us in direction of our dedication to be extra open, clear and inclusive. We recognise that there’s nonetheless much more work to do.

Due to my colleague Dr Dan Potter for his feedback on this weblog publish.