The primary public style of FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE may hardly have transpired in additional extraordinary circumstances. As Brian Eno sang menacingly of “rock and fireplace” and “gasoline and dirt” amid an ominously swelling storm of distorted synths, smoke lingered within the nighttime air and ash rained down from the heavens. He was standing on the traditional stage of Athens’ Odeon of Herodes Atticus, within the shadow of the Acropolis, and these weren’t particular results. Wildfires had been ravaging the Greek countryside, and when he cautioned that “these billion years will finish”, his voice dropped in a potent mixture of indignant admonition and determined resignation. The track felt like a warning from the gods.

The event was the inaugural reside efficiency final summer time by Brian and youthful brother Roger, in celebration of their debut full-length collaboration, Mixing Colors. Its well timed launch in March 2020, because the UK’s preliminary Covid lockdown started, allowed its light solo piano instrumentals to recast our sudden, alien vacancy as a welcome alternative for a breather. That premiere a 12 months later of “Backyard Of Stars” – and “There Had been Bells”, which engages with related themes – occurred in no much less serendipitous circumstances, albeit, given their issues, in an appropriately much less soothing method. “Right here we’re,” Brian commented from the stage, “on the birthplace of civilisation, watching the top of it.”

FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE’s recorded variations keep, just like the album’s subject material, loyal to the sound of that night time. “Backyard Of Stars” once more finds Leo Abrahams on guitar, Pete Chilvers on keyboards, and Roger on accordion– plus the latter’s daughter, Cecily, including her voice – and its livid midsection flaunts the form of visceral sound design favoured by sombre, supernatural Netflix dramas. “There Had been Bells”, in the meantime, begins with birdsong and cosmic gong-like synths, Brian plaintively describing a summer time’s day on which “the sky revolved a pink to golden blue” earlier than his somnolent temper slowly darkens. With a rumbling within the background, he conjures up “horns as loud as struggle that tore aside the sky”, turning to biblical imagery of Noah’s flood earlier than gloomily concluding, “In the long run all of them went the identical approach”. The shortage of an apocalyptic backdrop does nothing to minimize both track’s impression.

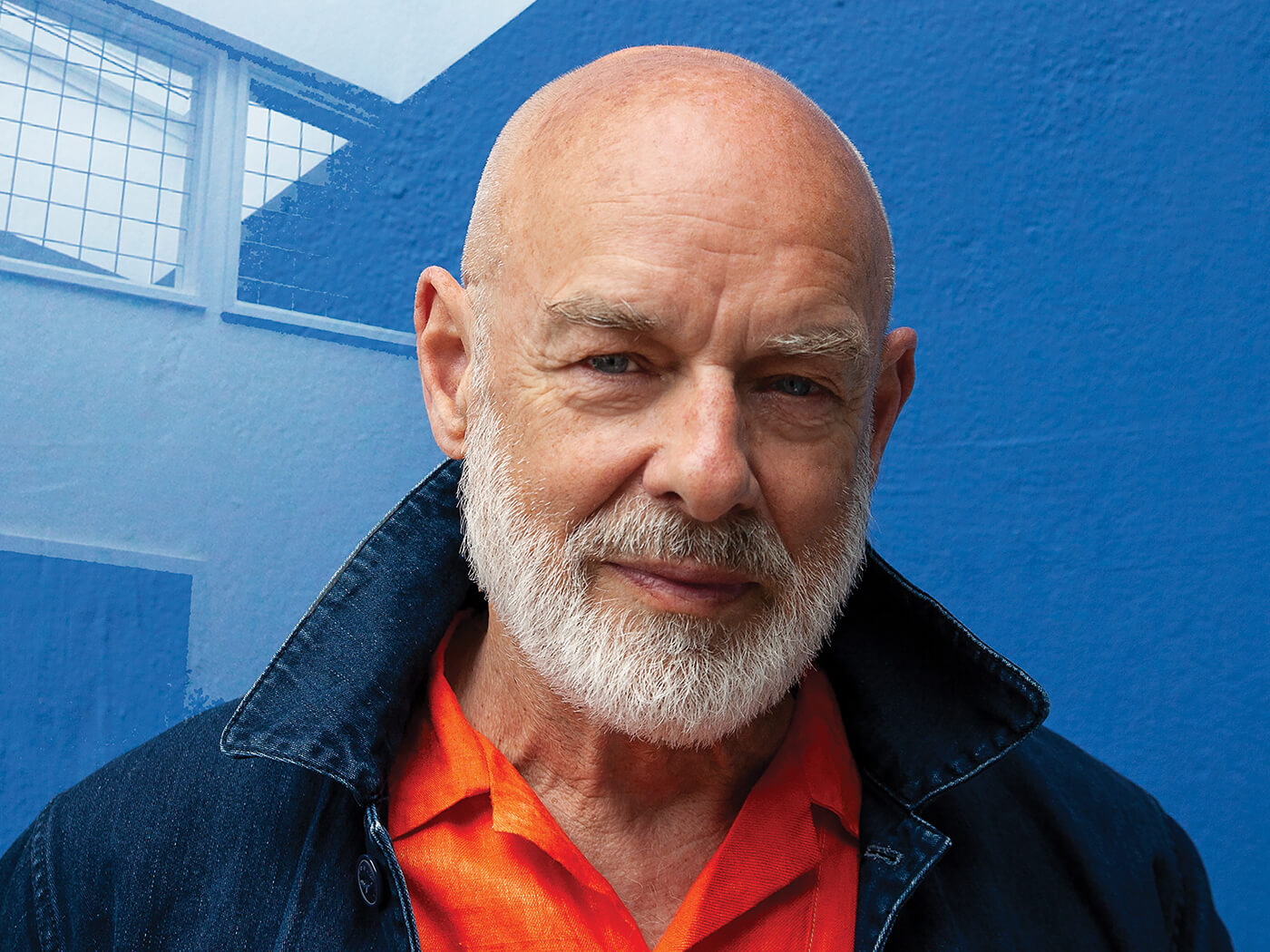

In simply the span of a pandemic, Brian seems to have renounced Mixing Colors’ escapist tendencies, his agenda no longer solely extra urgent but additionally grounded in actuality. This isn’t with out precedent: at factors, 2005’s One other Day On Earth tackled terrorism and 2016’s The Ship addressed struggle, and with their emphasis on vocals, these albums additionally arguably signify this new work’s most evident musical forerunners. However the man generally often called Mind One has now, if possibly grudgingly, accepted {that a} compassionate, intimate, much less cerebral strategy could also be simpler at urgently conveying the dismal ramifications of the local weather emergency to which many people, some wilfully, appear oblivious.

FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE subsequently makes little try and refashion the world in both a flattering or reassuring gentle, as an alternative documenting a considerate, candid response to our surroundings’s more and more speedy disintegration. He calls this “an exploration of his emotions”, and any affect he seeks is emotional. Avoiding sentimentality, this high quality unexpectedly seems to be important to the album’s success.

At occasions, like Mixing Colors, FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE invitations us to revel warmheartedly within the magic surrounding us, whether or not in broad brushstrokes, recalling the “final gentle from that previous solar”, a probably nostalgic allusion to Frankie Laine’s “Fortunate Outdated Solar” on the sparse, subdued, jazz-inflected “Sherry”, or zooming in with marvel on nematodes early in “Who Offers A Thought”. As he places it at first of “We Let It In”, a brooding however stunning lullaby whose synths breathe and growl like residing creatures, “The soul of it’s working homosexual / With open arms by golden fields”.

This awe at nature isn’t solely lyrically conveyed. Maybe essentially the most highly effective weapon Eno now possesses is his still-underrated voice, which he employs right here admirably to speak the sentiments at FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE’s coronary heart. These aren’t the playful, generally processed, chameleon-esque strains of Earlier than And After Science, although voices are sometimes handled, together with his daughter Darla’s on “I’m Hardly Me” and his personal on “Backyard Of Stars”, the place its faintly robotic character advances an already unsettling tone. Largely his register, deepened by age, is luxuriously lugubrious, because it was on The Ship. Typically he’s gentle and consoling (“Sherry”, “Icarus Or Blériot”), at others nearly choral (“We Let It In”, the hymnal “These Small Noises” with Jon Hopkins). On the introductory “Who Offers A Thought” and the nebulous “I’m Hardly Me” he even makes a convincing Ratpack crooner.

His velvet pipes and gracious harmonies, nevertheless, can’t cover how, befitting its themes of imminent disaster, that is incessantly uneasy listening. “We Let It In”‘s “golden fields” finish “in attractive flame” and, for all its glorification of creation, “Who Offers A Thought” encapsulates the contrasting melancholy wherein the album’s drenched. “There isn’t time today for microscopic worms”, Brian continues forlornly of these nematodes, his melody descending like a sigh, “or for unstudied germs of no industrial price”. If he begins by buzzing his notes as if mendacity in a scorching bathtub, lavish swathes of synths and Abrahams’ hazy guitars are quickly disturbed by a random, percussive knocking – like water slapping the facet of a creaking, sinking boat – and snatches of unearthly radio alerts. By the point a wistful solo trumpet punctures this mournful ocean of sound, the track’s plain class has been holed by remorse beneath the water line.

One thing comparable could possibly be mentioned of “Icarus Or Blériot”, whose title, nodding to the legendary Greek who flew too near the solar and the French aviator who was first to cross the Channel, extends a philosophical query posed insistently, and extra instantly: “Who’re we?” and, later, pointedly, “Who had been we?” Although its pulsing synths sound like distant planes and Abrahams’ guitars may go well with in the present day’s ambient Americana, any prettiness is undermined by unresolved stress and a scattering of transient bursts of dissonance.

Admittedly it’s among the many extra peaceable tracks, and never the one one loosely indebted to his earlier ambient excursions. Most of those “songs” are amorphous, devoid of rhythm, held collectively by Eno’s melodies, and all sides closes with an instrumental (of kinds). The celestial “Inclusion” ebbs and flows on a present of Roxy affiliate Marina Moore’s strings, and “Making Gardens Out Of Silence” is an eight-minute piece of generative music commissioned for the Serpentine Gallery’s ongoing Again To Earth challenge, its distorted, pitch-shifted voices echoing by one among his extra conventional soundscapes. It’s much less a finale than a swansong.

This, absolutely, is by design. That FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE’s Greek harbingers had been chilling provided little consolation beneath the nation’s sweltering skies, and a 12 months later the album’s troubling sentiments have solely turn out to be extra indispensable. Brian may have chosen to hector us, however as an alternative reminds us of all we stand to lose whereas providing

a flavour of our inevitably forthcoming grief. Actually, the environment’s unnerving, nearly bleak, nevertheless it’s much more inspiring, and most of all poignant. If this seems to be our planet’s bittersweet requiem, we’ll have solely ourselves responsible. At the very least we’ll go down singing these unusual, haunting elegies. Foreverandever? Amen.